|

| Photo by Karen Osborn |

So, Every July 1st is the, now posthumous, birthday of NMNH curator Kristian Fauchald, who was one of the most prolific taxonomists publishing on polychaete worms of the 20th Century!

This began in 2015 following his death (see the NMNH blog: http://nmnh.typepad.com/100years/2015/06/1st-annual-international-polychaete-day.html

I have honored this tradition with polychaete posts!

2015: Five Things you probably didn't know about polychaete worms: http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/five-things-you-probably-didnt-know.html

2016: Five GREAT Polychaete Names!

http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/five-great-polychaete-names-for.html

I missed 2017 because I was out at sea with the R/V Okeanos Explorer!

http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/okeanos-explorer-communities-deep-sea.html

But I've blogged PLENTY about polychaetes to make it up!

A post about Polychaete Jaws!

http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/polychaete-jaws-and-proboscises-for.html

My post about "Who Named the Bobbit Worm?" (which actually involves Kristian Fauchald)

http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/who-named-bobbit-worm-eunice-sp-and.html

Stunning Polychaete Photos by Arthur Anker!

http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/off-topic-panoply-of-polychaetes-photos.html

and Gorekia, a polychaete which lives INSIDE an urchin!

http://echinoblog.blogspot.com/2011/02/gorekia-worm-that-lives-inside-sea.html

So, for 2018 I am BACK for #POLYCHAETE DAY! So for this year.. a fun topic:

POLYCHAETE WORMS THAT SWIM!!

So, #2 to #5 are pelagic taxa.. that is they live exclusively (or mostly) in the 3-dimensional oceanic space ! They generally don't live on the bottom of the ocean floor. and so, they have adaptations which help them to live in this unique and vast area! as we'll see...

5. TOMOPTERIS!

First up are some of my FAVORITE swimming worms! Those in the genus Tomopteris!These are apparently VERY successful with a widespread distribution all around the world. There are apparently 35 to 50 species in this genus! About 15 of these occur in the subgenus Tomopteris (Johnstonella) which I suspect means there is some contention over how many there are..

BUT I can tell ya' this much! The NAME Tomopteris is Latin for "Split wing" which alludes to the paddles on each of their little legs! and the fact that it is apparently "cut" into two halves..

Tomopteris is apparently a PREDATORY worm, with at least one species indicated as a predator on arrow worms !

and as seen in many swimming species they are BIOLUMINESCENT! I don't have great shots of their glowie powers..but they ARE very photogenic animals.. so here's some video...

4. Alciopid Worms!

|

| Image by Karen Osobrn NMNH StreamCode SMS: https://twitter.com/InvertebratesDC/status/881237769762349056 |

Alciopid worms are most likely to be PREDATORY. They have an ENORMOUS proboscis which is presumably used to feed ON other prey...

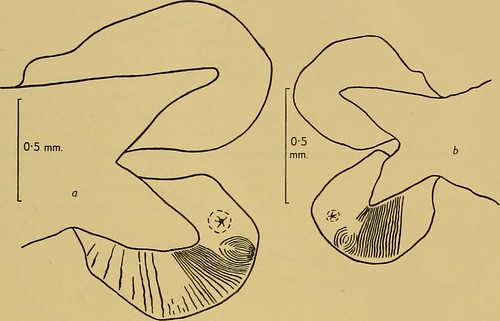

and They are known for having ENORMOUS EYES which are complex in a manner analogous to vertebrate eyes with lenses, irises, corneas and such.. So, they actually have well-developed VISION which is thought to assist in prey avoidance..

Here is a GORGEOUS chart on alciopid eyes via the Biodiversity Heritage Library Twitter: https://twitter.com/CarinaDSLR/status/575528089242959872

here was a nice back and forth about this deep-sea alciopid worm on Twitter!

BIG eyes on this one! An alciopid polychaete in our Pacific abyssal samples #WormWednesday #ABYSSLINE pic.twitter.com/A9QQbKUQ9z— Helena Wiklund (@helena_wiklund) September 27, 2017

Here's some swimming video! (thanks to Jackson Chu!)

3. The Deep-sea Pig Butt Worm! Chaetopterus pugaporcinus

I'll be honest. There's not much that I can add to this which wasn't already said by MBARI when the species was described:https://www.mbari.org/a-worm-like-no-other/

These are part of a genus of segmented worms called Chaetopterus, most of which aren't actually swimming species.. They kinda look like this: Many of them live in a paper-like tube..

This pelagic species was unusal in having swollen segments wich gave it an unusual appearance...And yes..the Latin name epithet "pugaporcinus".. is LITERALLY translated as "Pig Butt"

2. Swima bombaviridis! Swimming bomber worms! and relatives...(the Acrocirridae)

So, this is kind of a "two for one" deal because members of this one family of swimming polychaetes, the Acrocirridae actually have TWO very interesting members

Here were the "Squid worms" Teuthidodrilus samae whose very formidable appearance got them a notable write up in National Geographic among other places../ (https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/11/101124-squid-worm-new-species-science-teuthidodrilus-biology/)

and some "Squid Worm video!

Here was a nice video of that discovery via California Academy of Sciences & MBARI!

Time for a Swima! #Okeanos recently saw this swimming polychaete, in aptly named genus, Swima. Join us for another dive later today! pic.twitter.com/VAOy9WviOY— NOAA Ocean Explorer (@oceanexplorer) September 19, 2017

and of course..we have seen other members of this group on Okeanos Explorer..

|

| Engima Seamount 2016: https://twitter.com/WPolyDb/status/724026014725099520 |

FINALLY.. the last category of swimming segmented worms is kind of a mixed bag. This includes worms while swimming which are NOT a specific group and NOT a group of worms that swims its entire life..

This is the unusual phenomena in polychaetes known as EPITOKY!

This is the reproductive phase for many polychaete worms in which they physically change and shift into a swimming form or mode! these species typically are adapted to bottom living.

Presumably this sudden ability to swim goes hand in hand with dispersal of the reproductive products.

Here for example.. we have an example of a sexually mature worm carrying its products while also swimming! aka engaging in pelagic life mode.

This change in life mode can be a bit of a surprise when your 2 foot long bristle worms are suddenly swimming around like giant snakes!

In the Indo-Pacific region, there are HUGE numbers of these epitokes swimming around in the water column and apparently, they are QUITE tasty..

Although prepared in many different ways, sometimes its apparently best to just have them on toast!

|

| from the original blog: http://mrlavalava.blogspot.com/2005_11_01_archive.html |